If you only see one episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation I recommend Season 2’s The Measure of a Man. The story breaks down as follows: a scientist asks permission to dismantle android crew member Lt Cmdr Data for purposes of research and replication. Data refuses leading to a legal battle over his right to self-determination. It’s a classic case of Science vs Ethics; the ability to do something countered by the moral case for doing it. Like the best science fiction, it echoes themes we’re still dealing with today like slavery/cheap labour and the Uncanny Valley.

If you only see one episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation I recommend Season 2’s The Measure of a Man. The story breaks down as follows: a scientist asks permission to dismantle android crew member Lt Cmdr Data for purposes of research and replication. Data refuses leading to a legal battle over his right to self-determination. It’s a classic case of Science vs Ethics; the ability to do something countered by the moral case for doing it. Like the best science fiction, it echoes themes we’re still dealing with today like slavery/cheap labour and the Uncanny Valley.

I bring this up as a similar debate is underway at the EU level after the legal affairs committee passed a report to parliament looking to establish an agency for regulating the robotics sector. The sci-fi fan in me is delighted conversations like the definition of ‘electronic personhood’ are being had at parliamentary level but not everyone is convinced now is the time for it to be happening.

Authored by Mandy Delvaux, an MEP from Luxembourg, the report weaves together mentions of Frankenstein, Pygmalion and Isaac Asimov’s laws of robotics to search for an appropriate definition of what distinguishes the ‘smart robot’ we should treat with respect and courtesy from the toaster, fridge and thermostat we don’t.

“A growing number of areas from our daily lives are increasingly affected by robotics,” wrote Delvaux. “In order to address this reality and to ensure that robots are and will remains in the service of humans, we urgently need to create a robust European legal framework.” Rightly so.

Framework

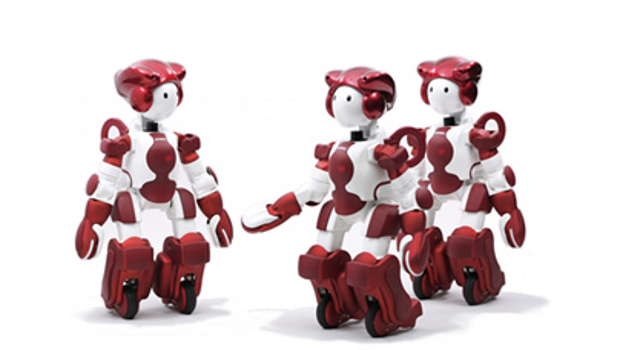

That proposed framework starts with a definition of what constitutes an electronic person and extends through how they are managed through to what to do and who to blame when they fail or do something wrong.The current thinking is that definition includes the ability to gather data through sensors and make use of it; the ability to learn unaided; have a physical structure; and to be able to adapt behaviour and actions according to its environment.

At a deeper level, the report goes beyond the physical makeup of robots to tackle the principles on which they are built, specifically the right to autonomy and justice, and on the part of the designer, a commitment to benevolence and a sense of social responsibility. No Killbots then, but a kill switch is an essential feature. Maybe that means autonomy comes with a large asterisk.

While the top line issues of definition and regulation of design and programming there are some side issues I hadn’t thought of as being central to robotics. First among them is what to do with data gathered by robots. With the spectre of the EU’s thorough General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) looking large over 2017, operators – domestic and industrial – will need to have a case for what information their robot collects and come up with a secure way of storing it.

This is a trivial issue for non-networked robots with limited capacity to adapt to different circumstances. On the other end of the scale you have robots engaged in routine research tasks like record retrieval (discussed with author Chrissie Lightfoot on TechRadio), or grocery selection (as per Amazon) where personal or commercially sensitive data will be handled on a daily basis. ‘Privacy by design’ is a phrase we’ll be hearing a lot more of in the coming years and its application will be keenly felt in robotics.

A second issue operators should be aware of is insurance. Again, starting on the factory floor, should a robot malfunction and lead to injury to a human there is liability to consider. The changing dynamic of the factory floor will mean that health insurance schemes could become a thing of the past but that doesn’t mean employers should be able to walk away providing staff coverage. Robots don’t catch the flu but they can break down and require spare parts, not to mention what happens should something happen to an operator on account of a design flaw or inadequate programming.

This leads to a third problem: how to quantify the cost savings made from a transition from a largely human to a largely automated workforce and the impact on employer contributions to the state. Delvaux suggests a reporting structure should be in place where employers are obliged to declare savings made through the use of AI and automation. How that is going to translate into some sort of revenue contribution, I’m not sure. If you reduce your workforce across departments, how many job losses can be directly attributed to automation versus natural wastage? It’s doubtful business owners will be fretting over the minutiae of their social security bill or even be able to quantify how much they owe for staff they don’t even have. Meanwhile the dole queues get longer as jobs from mechanics to researchers are taken out of human hands.

As I said, there are some who say this discussion is being had way too soon. Delvaux reckons she is about 10 years ahead the curve, but even this may be an optimistic view. Patrick Schwarzkopf, head of German industry body VDMA puts that number at about 50. “We think it [the agency] would be bureaucratic and stunt the development of robotics,” he said.

While I agree that the timeframe for the Fourth Industrial Revolution might be overstated, there’s nothing to say it won’t arrive in a form we just haven’t conceived of yet. In which case, it’s no harm at all to have a plan B in place. Especially if today’s plan B happens to be tomorrow’s plan A. If that computes.

Subscribers 0

Fans 0

Followers 0

Followers