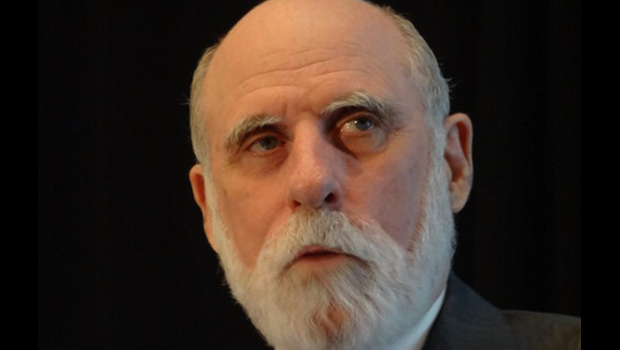

When Vint Cerf was invited to join Google in 2005 he was asked what job title he wanted. That’s the kind of treatment you get from one of the world’s biggest tech companies when you’re one of the ‘fathers of the Internet’.

“I thought about that for a while and said, what about Archduke?” Cerf, co-designer of the TCP/IP protocols and the architecture of the Internet, remembers.

“So they [Larry Page and Sergey Brin] went away and came back and said ‘you know what, the famous Archduke is Ferdinand, and he was assassinated in 1914 and it started World War I. That sounds like a bad title, how about you be our chief internet evangelist?’” Cerf says. “I said, ok I can do that. So that’s what I am.”

He shared two of them this week at an event at UNSW in Sydney hosted by AI Prof Toby Walsh.

Cerf surely stands out among the hoodie and t-shirt wearing staff at Google’s trendy offices, insisting on wearing the immaculate three piece suits which have become his trademark. His ideas are a little eccentric too, but are being taken super seriously by the search giant.

Digital dark age

“Every one of you has online a gazillion pictures and they’re just seem to be there and they don’t seem to go away so they’ll be there forever right? Wrong,” Cerf, dressed in a deep blue suit and waistcoat, light blue shirt and silver Paisley tie, said.

“Because they are substantiated in physical media, and physical media don’t necessarily last forever.”

While certain formats continue to be widely used (vinyl music sales were up 19% last year) others (compact disks) are less so.

“There are people in this room I’m sure who have a 5″ floppy disk gathering dust in their basements and wardrobes and they can’t find a floppy reader anywhere – well, in the Smithsonian or your local museum maybe. Same problem for 3.5″ floppy disks or CD-ROMs or DVDs, and disk drives whose interfaces you can’t find the plugs to connect in,” Cerf said.

The same is true of files and software. If an application can’t run on the operating systems of a decade from now, files become inaccessible. A software company might go out of business, taking its codebase down with it. Backwards compatibility is not guaranteed.

The result is what Cerf calls a ‘digital dark age’ and we are racing towards it, he said.

A century from now, those looking back to our current era may not be able to access the millions of images we store without thought on Facebook’s cloud servers. Unlike ancient manuscripts and cave paintings that have survived for thousands of years, today’s digital content could be lost forever, Cerf said.

“I’m a big fan of creating a regime in which we can assure ourselves that digital content will be moved from one medium to the other. And that we are able to preserve and run old software to correctly interpret the bits,” he said. “Preserving software is just as important as preserving the bits of data.”

Earlier this year the Internet Society embarked on a project to explore and define digital preservation principles, protocols and practices with Google’s backing.

Google’s Art & Culture group is also partnering with a nonprofit called Rhizome whose small software development team creates tools to emulate legacy browsers. The partnership has led to the emulation of three ‘games for girls’ from the 1990s.

But such efforts are a drop in the ocean of formats and file types headed for eternal incompatibility.

“Open source may help us in some respects but there is a digital dark age looming if we don’t [take action],” Cerf said.

IDG News Service

Subscribers 0

Fans 0

Followers 0

Followers