The news that a British Airways passenger jet collided with drone yesterday can’t be considered much of a surprise. I’d call it disgusting but inevitable. A boneheaded act of vandalism of the ‘laser pointer v cockpit’ variety.

The news that a British Airways passenger jet collided with drone yesterday can’t be considered much of a surprise. I’d call it disgusting but inevitable. A boneheaded act of vandalism of the ‘laser pointer v cockpit’ variety.

The short version is that on Sunday morning the nose of a BA jet made contact a drone as it made its final approach to land. No serious damage was reported and the aircraft was able to remain in service. At time of writing the drone hasn’t been recovered or, indeed, its operator identified. Flying a kite near an airport is a dumb idea, let alone a craft capable of doing significant damage to vehicles or infrastructure responsible for the safe passages of thousands of people every day. More than that, it’s illegal. One hopes the latter will happen and that they will have a large, hardbacked book thrown at them.

Could it happen here? Of course, and it possibly has already. Highly publicised incidents, however, have a habit of putting the issue of regulation into sharp relief – at least Ireland is not found wanting.

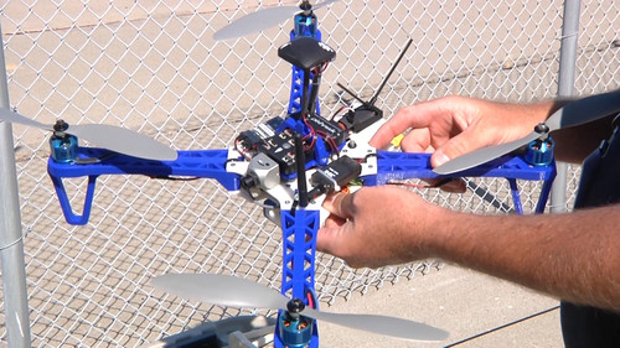

On 21 December 2015 the Irish Aviation Authority Small Unmanned Aircraft (Drones) and Rockets Order came into effect, providing a proper regulatory framework for automated aircraft weighing 1kg to 25kg. As of late last year any drones fitting into that size bracket had to be registered with the state and are subject to a number of restrictions on their use.

Under Irish law you cannot fly a drone within any controlled airspace (like an airport); within 5km of an aerodrome while it is in use unless permission has been given; further away than 30 metres to a person, vehicle or structure under control of the operator; less than 120 meters from a gathering of 12 or more people; beyond line of sight of the operator; beyond 300 metres from the operator; above 120 metres from ground/water level; nor can you drop an article from the craft – regardless of whether a parachute is used.

Registering is a simple process and a much more useful one than merely applying for a licence and waiting for a sticker in the post. On completing a form the user is given access to a map of Ireland showing in detail where they can and can’t fly safely. It’s a system based on helping people enjoy new technology while paying heed to factors they might not have thought important when making their purchase. It’s €5 well spent.

Bringing craft into a regulatory structure isn’t a complete solution to operators acting irresponsibly. For that we have to look for a technological solution. Intel’s work on collision detection is impressive but for the here and now an upgrade to software over hardware might prove a cheaper alternative and there is already a solution on the market that would work – although it comes from an unexpected quarter.

A few weeks ago a GPS-enabled smartwatch by the Irish company Watchovers arrived on my desk. It operates on a simple principle. The watch is linked to a smartphone via an app and uses GPS to show the device’s location at any time. The app’s controller can decide to implement ‘geofences’ where they get sent automatic alerts should the device stray beyond a prescribed area. What a perfect solution for drone operators. It’s easy to see how this could be integrated into the drone registration process. Download the app, install and associate a drone with a phone number, the smartphone tracks the drone using GPS and gets sent a warning when it enters prohibited airspace. What’s more, the phone could keep a record of the journey – should that become important later.

Regulation, location tracking and collision detection will do for human error in drone operation. As for the intent of operators in the first place… that’s why we keep the hardback books.

Subscribers 0

Fans 0

Followers 0

Followers